Australia has a great health system, but still has room for improvement - increased affordability; better universal access; reduced variability in health outcomes given social determinants; a shift of focus from treatment to prevention; and continuously enhanced quality of care.

Australia has one of the best health systems in the world, however, its position on Bloomberg’s 2019 Healthiest Country Index has slipped.1

Our health system faces similar pressures to others globally, including rising costs driven by increasing incidence of chronic diseases, an aging population, inequitable access to services, and gaps in workforce and infrastructure. In addition, changing customer expectations are driving a need for more personalised, digital, seamless and integrated care experiences.

While these trends are all well known, providers, payers and broader industry players are at varying levels of maturity in terms of adapting to the change - impacting the ability for system-wide reform.

Increasingly unaffordable

Whilst Australia has a world-leading health system, it is unfortunately becoming increasingly unaffordable. While 86 per cent of all Medicare services are bulk-billed2, and 10 per cent of our GDP is spent on healthcare (which is around the OECD average3), hidden within these statistics is the fact that many Australians pay out-of-pocket for Medicare services, and Australia is at the highest end of the OECD average for what individuals pay for their healthcare. Similarly, the Grattan Institute’s report on private health insurance (PHI) paints a bleak picture, with premiums rising while people drop their cover - about 100,000 fewer Australians have private hospital cover today than a year ago4.

Gaps in health outcomes

There is a gap in health outcomes across socio-economic groups as well between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous population. Research shows that lower socio-economic groups have higher instances of obesity and other chronic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes5. Western Sydney (NSW) is recognised as a hotspot for diabetes, with twice the incidence of the northern and eastern suburbs6. Indigenous Australians have a life expectancy 10 years less than non-indigenous Australians, driven in part by lack of access to healthcare7.

Focus is on the symptom, not the cause

Whilst consumers are increasingly focused on wellness and prevention, Australia’s health system is still geared towards treating illness - better suited to last century’s acute care needs than this century’s chronic disease incidence. Research shows that investment in prevention programs yields better health and cost-effectiveness outcomes than focusing solely on treatment. The challenge remains on how to increase funding for prevention for the future, whilst still paying for today’s treatment needs.

Investing in quality through innovation and research

Whilst the Medical Research Future Fund in 2015 is a step in the right direction, there is room to increase investment in new healthcare innovations which will drive consistent delivery and quality outcomes. Australia could position itself as a world leader in innovative medicines and diagnostics which not only deliver benefits in improved health consumer and patient experience, but also economic growth through investment and trade.

Shifting approaches to improve health outcomes and sustainability

Delivering patient-centric integrated care models combined with an increased focus on empowerment, wellness and collaboration is paramount for long-term sustainability and better health outcomes for all.

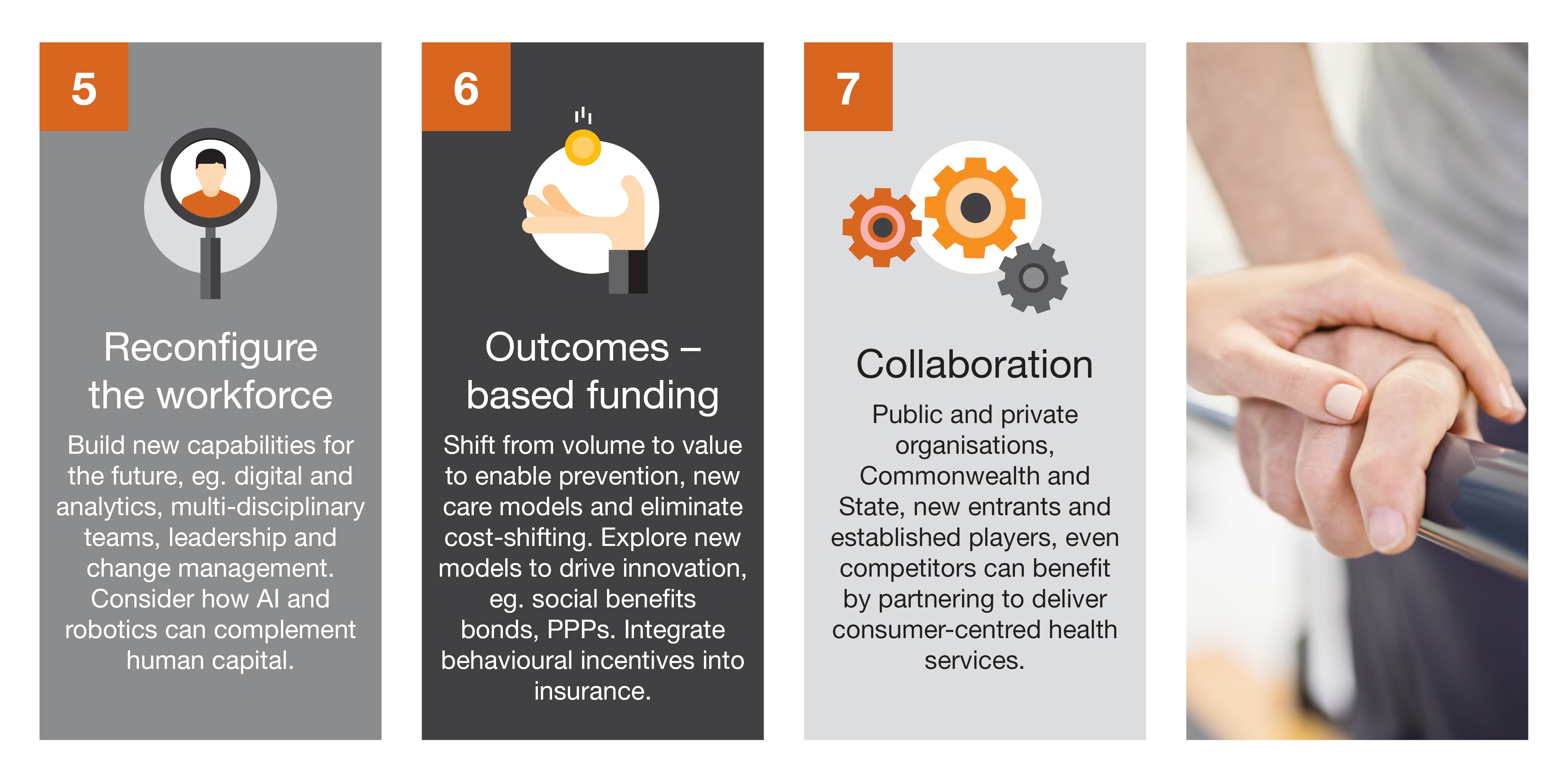

Challenges in Australia’s current health system can be reframed into opportunities for the future. In 2017, we identified seven focus areas for leaders to reform the health system8 all of which are still relevant today.

Extending on these, we have identified key practical actions and opportunities we believe should be taken over the next 12 to 18 months to accelerate our journey towards reimagining the future of health.

Focus area 1: Consumer empowerment and engagement

Action 1: Increase access to information to empower health consumers and improve transparency

Empowered health consumers, who take greater ownership of their journey, achieve better health outcomes.9 Consumers are demanding more transparency and better quality of service, by actively comparing experiences and seeking peer reviews. Governments should work towards increasing access to real-time, accurate health information and services so that consumers are able to make informed decisions. However, this must be balanced by the secure transfer of data (which addresses valid privacy concerns), while also engaging constructively with clinicians.

Action 2: Design and implement initiatives to build consumer trust

Consumer trust is more vital to brand survival than it's ever been, and the health industry is no exception. Research shows consumer trust in Australia’s PHI industry is deteriorating.10 Given the criticality of the PHI industry to Australia’s health ecosystem and Australia’s wider economy, rebuilding consumer trust will be vital in ensuring sustainability.

Focus area 2: Keeping people healthy

Action 3: Increase health literacy

Targeted health literacy campaigns are an effective way to drive desired behaviours and improve health outcomes. Populations should be segmented into risk categories (eg. age and health status dimensions) so to identify the two to three behaviours that would do most to improve the health of consumers in that cohort - for example, increasing physical activity or improving nutrition. These segment-specific insights, overlayed by behavioural economics, will then provide the focus for health promotion and prevention efforts.

Action 4: Leverage changing community sentiment through collective action initiatives

Leverage the changing community sentiment towards illness prevention by focusing on initiatives that harness collective actions - ranging from national policy settings to local community linkages and action. This collective action moves the responsibility for prevention - and health more broadly - away from the traditional expectations that these sit with government. Rather, it engages individuals, carers/families, academia, the private sector, and related industries to all take ownership and play a part. One initial area for investigation with a collective approach could be to revisit a set of National Prevention/Wellbeing Goals to set up a mechanism for measurement and monitoring prevention and public health investments.

Focus area 3: Right care, place and time

Action 5: Connect remote communities to health services through virtual care

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) analysis11 of ABS 2016 data showed that, on average, people in rural and remote communities were more likely not to see a GP due to physical access. Technology can address barriers often faced by rural and remote communities, such as infrastructure, distance and cost. Provision of consultations, referrals, scripts and test results by email, phone, FaceTime or Skype, as well as the enhanced use of the MyHealthRecord will connect rural, regions and remote areas to GP services. This approach will especially benefit Indigenous communities which are often hardest hit by lack of access to health services.

Action 6: Define standards to enable a connected health ecosystem

To better connect the health ecosystem and to deliver more personalised prevention and quality care, we need to improve digital exchange across electronic health records and health information technologies. Governments should collaborate with the health and health software industries to define standards for information exchange and system interoperability. By leveraging robust and interoperable data sets Government and health service providers can make informed decisions which better support a patient’s journey, enabling better patient and clinician experience, while also strategically planning for the health needs of the future.

Action 7: Improve accessibility and affordability of services closer to home

A report from the Australian Productivity Commission showed there were 3 million avoidable hospital presentations in the last financial year, where patients failed to see a local GP due to poor access.12 Research conducted by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found more than a million Australians put off seeing a doctor due to out-of-pocket expenses.13 Delays in GP visits increase the chance of more serious complications requiring costly hospital treatment. Improving the accessibility and affordability of services closer to home will be important in increasing the takeup of community health services and reducing the burden on public hospitals.

Action 8: Conduct a campaign to encourage care closer to home

Encouraging people to seek care closer to home by a team of allied health professionals ensures individuals are better supported for long-term health needs, such as mental health, rehab, aged care and special needs - increasing the individual’s quality of life as well as reducing the overall cost of care. An example is aged care where there is a clear 'win-win' to shift care out of the hospital. This could be supported by funding an Innovation Accelerator for pilot programs for seniors' care at a local level. The aim would be to help keep people in their preferred environment for longer, with a smooth transition through home, residential living, aged care, hospitals and palliative care, supported by integrating funding to make this seamless for the individual and commercially sustainable for providers.

Focus area 4: Innovation, digital and analytics

Action 9: Move toward Open Health, sharing information to support innovation

Over the next decade the emergence and adoption of new technologies in health such as robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) will rapidly change early detection, examination, diagnosis and prescription of personalised treatment plans founded in evidence based health.14 Improving care requires the alignment of broad base data analysis with appropriate and timely decisions, and predictive analytics can support clinical decision making and actions as well as prioritise tasks.

Similar to ‘Open Banking’, the Australian government should move towards implementation of the operating model and regulatory framework for ‘Open Health’. Open sharing of health information should drive innovation. Furthermore, increased access to health data and analytics can be used to inform policy and regulatory decisions on public health, shape investment in programs, preventative campaigns and reduce health costs through establishing predictable recovery pathways for chronic diseases (eg. care pathways that are both cost and clinically effective).

Action 10: Cybersecurity - data protection, privacy, security and consents

Electronic health records and internet connected medical devices will play a key role in transforming the health system - but each connected bit of information and device is a potential gateway for cybercriminals. As a greater amount of personal health information is shared between organisations, data privacy, security and consents will become critical. In the digital health age managing patient data through robust and sophisticated cybersecurity capabilities will be paramount to building patient trust and managing risk.15

Focus area 5: Workforce of the future

Action 11: Develop a strategic workforce plan

The health workforce of the future will require upskilling in new technologies, addressing potential resourcing gaps, and collaborative mindsets and ways of working. Developing a strategic workforce plan will optimise employment models (including the use of contingent labour/agency staff) to ensure healthcare organisations have the right skills, in the right place, at the right time to meet demand. These plans will need to also consider the importance of key enablers such as leadership, culture, governance and integrated planning to compliment the more tangible workforce challenges.

Action 12: Design alternative education pathways and partnerships

Healthcare and social assistance workforce demand is expected to increase by 14.9% over the next four years. These trends present critical challenges, predominantly for the nursing workforce, with an expected undersupply of 123,000 nurses by 2030.16 Healthcare workers and educational providers need to collaborate to design alternative educational pathways and partnerships in order to ease supply chain constraints. Investing in growing training pathways from secondary schools straight into careers in health will help to improve attractiveness and fast-track candidates into the workforce. Organisations should also strive to reflect the community through a diverse and complementary workforce.

Focus area 6: Outcomes-based funding

Action 13: Define a framework for an outcomes-based funding model

Guiding principles and a framework for an outcomes-based funding model needs to be defined, with broad consultation from all health industry stakeholders. The current funding model for health and aged care across states and territories is based on division of responsibilities and interjurisdictional agreements, ie. an input-based funding model that struggles to address prevention, chronic disease and broader wellness. Pooling funding could support moving from volume to value, enable new care models and take-up of digital, eliminate cost shifting and better support prevention campaigns, with an appropriate debate on the role of out-of-pocket/consumer payments.

Action 14: Identify alternative funding mechanisms/sources

The health and life insurance markets are an example of where alternative funding mechanisms can be applied, monetising incentives for early intervention and healthier behaviours. Converging the life and health insurance markets, with cohesion in regulatory frameworks, could accelerate the creation of new products for consumers across the lifecycle (including for younger segments) that provide a wider range of coverage and incentives for prevention and behavioural change, as well as support for proactive health and chronic disease management. Through this, there are opportunities to provide better transparency and value for money for the consumer, and support better sustainability and affordability across the public-private health system.

Focus area 7: Collaboration

Action 15: Identify opportunities to collaborate within health

A collaborative approach across private and public healthcare providers and government is needed to drive better health outcomes and ensure sustainability. The recent PHI reforms provide a good example of how this can be successfully conducted: multiple stakeholders (including insurers, private hospitals, the AMA and medtech) worked together to design and implement reform where focus was on the industry as a whole, and not just through a ‘win-lose’ lens for individual players. Whilst all acknowledge much more work is needed, the principle of collaboration and the need for compromise should be apparent.

Action 16: Identify opportunities to collaborate with other industries

Collaboration with other industries will be key as health becomes more holistic and integrated end-to-end care for the consumer. The increasing role of technology in healthcare will make collaboration vital as sectors work together to make advances in areas such as medical technologies, AI-enhanced surgeries, and data analytics - supported by the right infrastructure, such as 5G. Collaboration with the banking sector will be important for the growing healthcare payments market which is estimated at A$180 billion.17 Likewise, retail and consumer industries increasingly have opportunities to support better nutrition and fitness. Finally any organisation can play a role in promoting health and wellbeing for their employees, in particular supporting better mental health.

Stakeholder actions

Through all these actions, we have the opportunity to deliver better health outcomes to all, at more sustainable and affordable costs - ultimately investing in our nation’s greatest asset: its people.

1 Miller, L. J. and Lu, W., These Are the World’s Healthiest Nations, Bloomberg, viewed June 2019

2 Australian Government Department of Health, Annual Medicare Statistics, viewed June 2019

3 Parliament of Australia, Health in Australia: a quick guide, viewed June 2019

4 Duckett, S., Private health cover is in a death spiral, Grattan Institute, 29 April 2019

5 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia, 2017

6 PwC analysis, ABS National Health Survey 2017-18

7 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Life Expectancy, viewed June 2019

8 PwC Australia, Reimagining Healthcare in Australia, 2017

9 NPS MedicineWise and Consumers Health Forum of Australia, Engaging consumers in their health data journey, March 2018

10 Roy Morgan, Health insurance industry distrusted by Australians, 28 March 2018

11 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Rural and Remote Health, 2017

12 Australian Government Productivity Commission, Health services across Australia, 2018

13 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s health 2018, 2018

14 PwC Australia, Adopting AI in healthcare: why change?, February 2019

15 PwC Australia, Practical Innovation: Closing the social infrastructure gap in health and aging, February 2018

16 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Health Expenditure Australia 2016-17, 2018