{{item.title}}

Key takeaways

There was a scene in the 1999 cyberpunk blockbuster film The Matrix that predicted a future technology with eerie accuracy. No, it wasn’t the ability to dodge bullets in slow-motion. The moment in question involved the main character, Neo, learning hand-to-hand combat.

Instead of spending half a lifetime rigorously training under the tutelage of a master, Neo was able to acquire several different martial art disciplines within hours. All that was required were some computer discs, a sewer-dwelling spaceship from the year 2199, and the existence of – and the ability to hack into – a mind-bogglingly sophisticated virtual world run by killer robots.

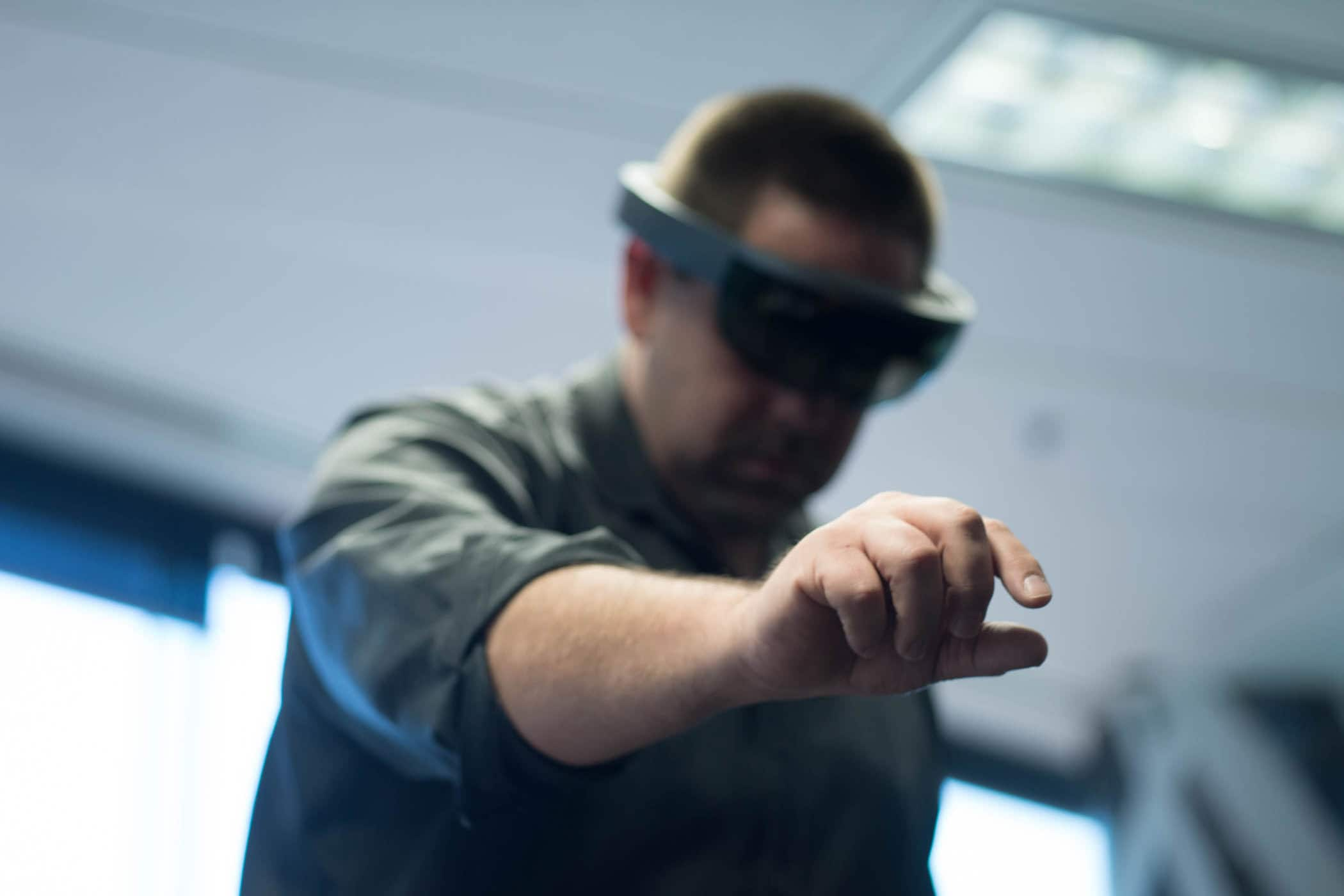

Of course, much of this future scenario will probably remain confined to the world of science fiction (we hope). But the film’s prediction that virtual reality (VR) will help us learn or train with speed and efficiency proved prescient. With the consumer editions of VR hardware such as Oculus Rift and HTC Vive reaching public release this year, and a whole slew of startups developing learning-focused VR content platforms, the race is on to transform the worlds of education and training.

Virtual reality’s immersive qualities have been researched for decades. In the mid-1990s, several years before The Matrix was released, controlled studies were conducted to test VR’s effectiveness as a form of exposure therapy – which enables sufferers to confront the object of their fear in a controlled environment – treating conditions such as acrophobia, a fear of heights. While the results were very promising, broadly waning consumer interest in the technology at the time saw it largely fall out of the public eye.

That all changed in the last few years. Reignited interest in VR as a mainstream consumer product has simultaneously rejuvenated the prospect of the technology as an effective way to deliver education and training.

Examples of sectors where VR-based training initiatives have been developed include combat simulation in the military, surgery procedures in medicine, safety modules in the mining industry, and as a ‘contact-free’ training program for American football players recovering from injury.

On the education side, Google recently launched Expeditions, a tool that builds on the company’s Cardboard platform to provide children with a ‘field trip’ experience from the classroom. Google Cardboard opens up VR to anyone with a smartphone and a pair of scissors. To try the platform, users simply order a cardboard headset (or build their own), insert a smartphone into the display slot and pair it with the Google’s Cardboard VR app.

Elsewhere, environmental groups experimenting with VR have reported audiences becoming much more engaged on environmental topics such as ocean acidification, deforestation and energy conservation.

Much of the marketing for these training-focused VR platforms draws on a commonly accepted principle that experiential training is more effective, and the information retained for a much longer period than more traditional methods, such as listening to a lesson and taking notes, reading a textbook, participating in a group discussion or watching a video presentation.

For example, in a Fortune magazine story announcing that a US children’s hospital was using VR to train medical personnel, the healthcare system’s CEO, Narendra Kini, said that up to 80% of VR-taught information could be retained a full year after training, whereas traditional methods saw only 20% of information retained after a week.

According to Kini, the sensory input from VR had the effect of creating new memories in trainees, familiarising them as if they had performed the procedure before.

Experiential training, and VR’s ability to unlock it, recalls a (hotly debated) diagram called the Cone of Experience or the Pyramid of Learning. Developed in the 1960s by American education theorist Edgar Dale, it ranks the various ways of teaching by their efficacy, with lectures and text-reading deemed the least effective methods and pure experience of the subject itself considered the most effective. Framed in this manner, VR shows great promise.

Regardless of whether or not a hierarchy of teaching techniques exists, ranking systems of learning in such a manner omits a crucial underlying issue with educating the masses: scale.

Lectures and text readings – with their ability to be either mind-expanding or mind-numbing for students and teachers alike – have survived as long as they have because of their ability to convey a sizable amount of information to a large audience at manageable costs.

Recent digital initiatives have improved this economy of scale even further, digitising course learning and distributing it cheaply online. But the resources deployed, and the core teaching experience, can often remain largely unchanged.

In this context, the emerging ecosystem of VR consumer hardware is very exciting. By bringing down its own barriers to entry, VR is unlocking a whole new tranche of experiential training methods, allowing it to be developed, refined and distributed in a highly scalable fashion.

It remains to be seen if VR can match or outperform traditional techniques in the education space. But recent projects and experiments show things are certainly moving in the right direction.

What’s more, if VR-boosted teaching does allow us to learn faster and more effectively, many other wider benefits could be realised, including shorter course durations, streamlined curriculums and structural cost savings. More broadly, the ability for workforces to be retrained and redeployed faster could see more nimble adaptations to changing labour markets and skill shortages.

Perhaps a real-life version of The Matrix wouldn’t be so bad after all…

References

© 2017 - 2026 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.